Leadership is often most visible in moments of success, but it is most consequential in moments of failure. When leadership breaks down, the effects ripple far beyond the individual at the top. Teams fracture, institutions weaken, trust erodes, and long-term damage can outlast the leader’s tenure by years. Understanding what happens when leadership fails is essential for preventing repeat cycles of dysfunction and rebuilding stronger systems.

Trust erodes first

The earliest and most damaging consequence of failed leadership is the loss of trust. People look to leaders for clarity, fairness, and consistency. When leaders act dishonestly, avoid accountability, or prioritize self-interest over the collective good, confidence collapses.

Once trust is broken:

- Employees disengage or comply minimally

- Citizens become cynical toward institutions

- Stakeholders question every decision, even good ones

Rebuilding trust is slow and fragile. Losing it can happen in a single moment.

Decision-making becomes reactive or paralyzed

Failed leadership often leads to poor decision-making in two extreme forms:

- Reactive chaos: leaders make impulsive choices to protect themselves rather than the organization

- Paralysis: fear of criticism or exposure leads to inaction, even when action is urgently needed

In both cases, opportunities are lost, risks grow, and problems compound instead of being resolved.

Accountability disappears—or becomes weaponized

In healthy systems, leaders model accountability. When leadership fails, accountability either vanishes or becomes selective:

- Mistakes are hidden, denied, or blamed on subordinates

- Loyalists are protected regardless of performance

- Critics are punished rather than heard

This creates a culture where truth is dangerous and silence feels safer than honesty.

Culture decays from the top down

Culture follows leadership behavior, not mission statements. When leaders tolerate unethical conduct, favoritism, or incompetence, those behaviors spread.

Common signs of cultural decay include:

- High turnover among capable people

- Normalization of “getting by” rather than doing well

- Loss of pride in work and shared purpose

Eventually, mediocrity becomes the standard, not the exception.

The most capable people leave

Strong performers tend to leave failed leadership environments first. They recognize stagnation, lack of integrity, or unfair systems early, and they have options.

What remains is often:

- Burned-out individuals who feel trapped

- Those rewarded for loyalty over competence

- A shrinking pool of innovation and initiative

This accelerates decline and makes recovery harder.

Short-term stability replaces long-term vision

Failed leaders often focus on preserving appearances rather than building sustainable futures. Metrics are manipulated, risks are deferred, and uncomfortable truths are ignored.

This leads to:

- Structural weaknesses hidden beneath surface success

- Crises that emerge suddenly and severely

- Organizations that look stable until they collapse

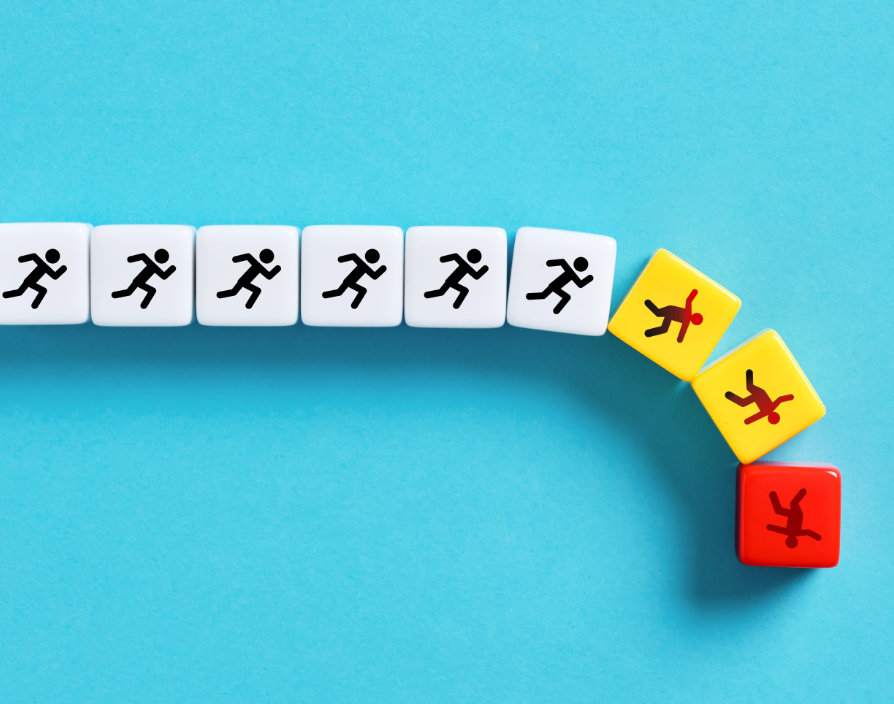

Leadership failure is rarely dramatic at first; it is gradual and cumulative.

The cost extends beyond the organization

When leadership fails in governments, corporations, schools, or nonprofits, the damage spreads:

- Communities lose services or jobs

- Public confidence in systems declines

- Future leaders inherit weakened institutions

Leadership failure is never contained; it always has human consequences.

Recovery requires more than replacing a leader

Removing a failed leader is necessary, but insufficient. True recovery requires:

- Honest reckoning with what went wrong

- Structural reforms, not cosmetic changes

- Leaders willing to listen, admit mistakes, and rebuild trust

Without this, failure simply resets under a new name.

Conclusion

When leadership fails, systems don’t just stall; they decay. Trust erodes, talent leaves, culture weakens, and the cost is paid by those with the least power to fix it. Yet failure also offers clarity. It exposes what leadership truly is: not authority, charisma, or control, but responsibility, integrity, and service.

The question is not whether leaders will make mistakes. The question is whether they will face them, and whether the systems they lead are strong enough to demand better.